Agency – the ability to act on one’s behalf, pursue one’s goals and exercise influence and voice – has become prominent in theories of change for empowering girls and improving their health, education, and economic outcomes (Eerdewijk et al., 2017; Kabeer 1999). Theories and frameworks have noted that the agency is dynamic and multi-dimensional, and typically includes varying combinations of constructs such as decision-making, goal setting, voice, negotiation, self-efficacy, mobility, leadership, participation, or collective action (Edmeades 2018; Eerdewijk et al., 2017; Jejeebhoy et al., 2010; Kabeer 1999). While cognitive development and opportunities for higher education and employment can result in an expansion of agency in adolescence for some, intensification of harmful gender norms and changes in social roles triggered by the onset of puberty may lead to loss of agency for some others (McCarthy et al., 2021). However, few published studies have mapped how agency changes over the course of adolescence among young people in developing countries. One study that has explored this question with longitudinal data from Zambian adolescent girls found that membership in high agency groups declined among older girls over time and that exposure to events such as early marriage was associated with loss of agency (McCarthy et al., 2021).

Agency – the ability to act on one’s behalf, pursue one’s goals and exercise influence and voice – has become prominent in theories of change for empowering girls and improving their health, education, and economic outcomes (Eerdewijk et al., 2017; Kabeer 1999). Theories and frameworks have noted that the agency is dynamic and multi-dimensional, and typically includes varying combinations of constructs such as decision-making, goal setting, voice, negotiation, self-efficacy, mobility, leadership, participation, or collective action (Edmeades 2018; Eerdewijk et al., 2017; Jejeebhoy et al., 2010; Kabeer 1999). While cognitive development and opportunities for higher education and employment can result in an expansion of agency in adolescence for some, intensification of harmful gender norms and changes in social roles triggered by the onset of puberty may lead to loss of agency for some others (McCarthy et al., 2021). However, few published studies have mapped how agency changes over the course of adolescence among young people in developing countries. One study that has explored this question with longitudinal data from Zambian adolescent girls found that membership in high agency groups declined among older girls over time and that exposure to events such as early marriage was associated with loss of agency (McCarthy et al., 2021).

In this brief, we use data from a unique longitudinal study of adolescents in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh conducted by the Population Council in 2015–16 (wave 1) and 2018–19 (wave 2), “Understanding the lives of adolescent and young adults study (UDAYA study)”,1 to explore changes in unmarried girls’ agency over time and with the transition to marriage and motherhood. We calculated agency indicators using factor analysis of unmarried girls’ survey responses to a series of questions related to their agency. The factor analysis yielded four different dimensions of agency which we named: 1) index of financial agency,2 2) index of decision-making agency,3 3) index of freedom of movement,4and 4) index of egalitarian gender role attitudes,5

Girls’ agency over time

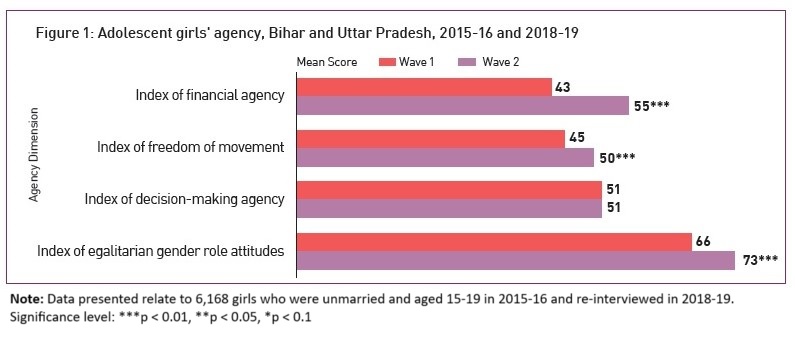

Agency was limited among all girls at wave 1 (Figure 1). Of the four dimensions of agency, girls scored the lowest on financial agency (mean score of 43 on a scale of 0-100) and the highest on adherence to egalitarian gender role attitudes (mean score of 66 on a scale of 0-100). All dimensions of agency, except decision-making agency, improved over time, confirming that age does indeed confer agency on adolescents. The mean score increased from 43 to 55 on the index of financial agency, from 45 to 50 on the index of freedom of movement, and from 66 to 73 on the index of egalitarian gender role attitudes. However, the mean score remained unchanged for the index of decision-making agency at 51 at both the waves.

Photo Credit: IHDS

Shifts in girls’ agency with the transition to marriage and motherhood

Shifts in girls’ agency with the transition to marriage and motherhood

Of the 6,168 girls who were unmarried at the time of the 2015-16 survey, 26 percent of girls got married and the remaining girls remained unmarried during the inter-survey period. Some 12 percent of all girls (and 47 percent of girls who got married in the inter-survey period) had begun childbearing by the time of the 2018-19 survey.

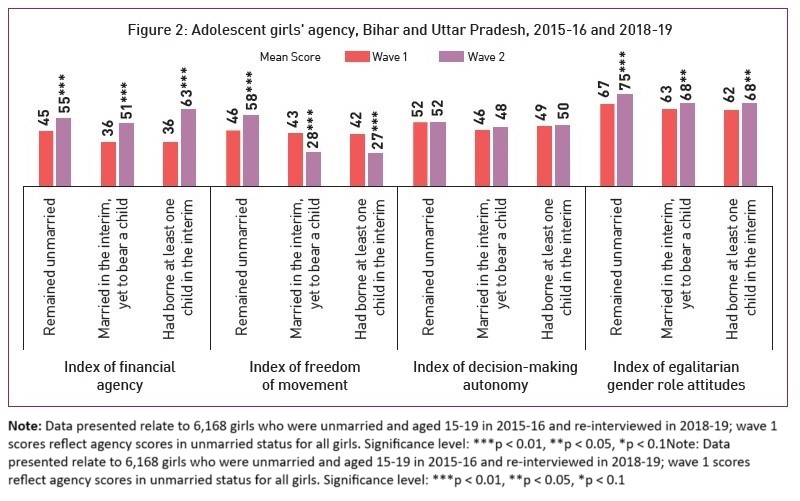

Life events such as marriage and motherhood affected adolescent girls’ agency in varied ways (Figure 2). Most dimensions of agency, except decision-making agency, improved over time among girls who remained unmarried during the inter-survey period, with girls gaining most on freedom of movement (mean score increased from 46 to 58), followed by financial agency (mean score increased from 45 to 55). Moreover, gender role attitudes became more egalitarian over time among these girls (mean score increased from 67 to 75).

Shifts in agency were mixed among girls who got married during the inter-survey period, regardless of whether they became a mother or not. As in the case of girls who remained unmarried, financial agency improved among girls who got married. But the gain in financial agency was larger among those who got married than those who remained unmarried, and even larger among girls who had begun childbearing during the inter-survey period (the mean score increased from 36 to 51 among girls who got married, but had not begun childbearing, and from 36 to 63 among girls who had begun childbearing). This positive association was confirmed in multi-variate regression analysis too.

Shifts in agency were mixed among girls who got married during the inter-survey period, regardless of whether they became a mother or not. As in the case of girls who remained unmarried, financial agency improved among girls who got married. But the gain in financial agency was larger among those who got married than those who remained unmarried, and even larger among girls who had begun childbearing during the inter-survey period (the mean score increased from 36 to 51 among girls who got married, but had not begun childbearing, and from 36 to 63 among girls who had begun childbearing). This positive association was confirmed in multi-variate regression analysis too.

Adherence to egalitarian gender role attitudes increased among girls who got married, as with girls who remained unmarried, although the increase was slightly smaller among the former than the latter (increase in mean score from 62-63 to 68 among girls who got married vs. from 67 to 75 among girls who remained unmarried).

Adherence to egalitarian gender role attitudes increased among girls who got married, as with girls who remained unmarried, although the increase was slightly smaller among the former than the latter (increase in mean score from 62-63 to 68 among girls who got married vs. from 67 to 75 among girls who remained unmarried).

Girls’ freedom of movement, on the other hand, declined significantly with marriage. The mean score on the index of freedom of movement declined from 42-43 to 27-28 among girls who got married during the inter-survey period, while it increased from 46 to 58 among girls who remained unmarried. This negative association was confirmed in multi-variate regression analysis too. This finding suggests that marriage may mark increased social isolation of adolescent girls.

Finally, as in the case of girls who remained unmarried, there was no change in the decision-making agency among girls who got married in the interim.

In brief, findings highlight that life events such as marriage and motherhood in adolescence do influence girls’ agency, although not consistently across different dimensions of agency. The reduction in girls’ freedom of movement with marriage and motherhood in adolescence can limit their social networks and opportunities to gain knowledge and skills to improve their health, education, and economic outcomes. Successful intervention strategies to empower adolescent girls need to directly address this negative influence, while augmenting the positive influence on their financial agency. Our analysis calls for future research attention to explore the determinants of observed changes, both improvements, and deterioration, in adolescent girls’ agency with marriage and motherhood in adolescence.

Endnotes:

References:

Edmeades J, Mejia C, Parsons J, et al. Conceptual Framework for Reproductive Empowerment: Empowering Individuals and Couples to Improve their Health (Background Paper). Washington D.C., International Center for Research on Women. 2018:1–76

Eerdewijk AV, Wong F, Vaast C, et al. White Paper: A Conceptual Model of Women and Girls’ Empowerment. Bill Melinda Gates Foundation 2017:1–12

Jejeebhoy S, Acharya R, Alexander M, et al. Measuring agency among unmarried young women and men. Econ Polit Wkly. 2010; 45:56–64

Kabeer N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev Change, 1999; 30:435–64.

McCarthy KJ, Wyka K, Romero D, et al. The development of adolescent agency and implications for reproductive choice among girls in Zambia. SSM Popul Health. 2021; 17:101011.

K.G. Santhya is an economist and demographer who has conducted studies on rights of youth, gender equity, women’s empowerment, reproductive health, and gender-based violence. She currently works as an independent researcher.

A J Francis Zavier is a Senior Programme Officer at the Population Council’s India Office and is a demographer, with more than 20 years’ experience in reproductive and sexual health research in India.