by Hope Xu Yan (University of Maryland), Dr Sonalde Desai (University of Maryland and NCAER) and Dr Debasis Barik (NCAER)

Land ownership is an important source of old age security, particularly in developing countries like India, where public transfers for old age support are limited (Lee & Mason, 2012). Controlling durable assets such as agricultural land can bring older people more say in household decisions, more access to household resources and support, and better well-being (Dharmalingam, 1994; Sudha et al., 2004). However, little attention has been paid to how gender inequalities may complicate the relationship between older adults’ asset ownership and intra-household bargaining power. In this context, it would be interesting to explore if older women and older men benefit equally from land ownership.

Agricultural land in India is typically controlled by the patriarch. Although legislations in 1956 and 2005 have partially established women’s rights to inherit land, in practice, very few Indian women own or control household land (Agarwal, Anthwal, and Mahesh 2021). This is because, first, granting women legal rights to inherit land does not guarantee their actual land ownership when the law is not enforced by the local community and family members. Second, women may only have nominal claims over the land or hold claims only jointly with the male family members. Hence, their claim could be fragile and they could lose their share in the event of an acrimonious property partition. Third, even with sole ownership, women may still be restricted from controlling the land when there are adult men in the household (Agarwal, 1994, 1998). The gender inequality in land ownership suggests that the generational power conferred on older men with land ownership may not apply to older women to the same degree, particularly if older women’s control over land is not formally codified or operationally established.

Agricultural land in India is typically controlled by the patriarch. Although legislations in 1956 and 2005 have partially established women’s rights to inherit land, in practice, very few Indian women own or control household land (Agarwal, Anthwal, and Mahesh 2021). This is because, first, granting women legal rights to inherit land does not guarantee their actual land ownership when the law is not enforced by the local community and family members. Second, women may only have nominal claims over the land or hold claims only jointly with the male family members. Hence, their claim could be fragile and they could lose their share in the event of an acrimonious property partition. Third, even with sole ownership, women may still be restricted from controlling the land when there are adult men in the household (Agarwal, 1994, 1998). The gender inequality in land ownership suggests that the generational power conferred on older men with land ownership may not apply to older women to the same degree, particularly if older women’s control over land is not formally codified or operationally established.

In a forthcoming paper in Feminist Economics, we use data from the India Human Development Survey to explore the gender asymmetry in how older people’s autonomy and well-being vary according to their ownership of and managerial control over households’ agricultural land. Specifically, we focus on variations based on a) ownership of land at the household level, b) individuals having their names on the land title, c) individuals having sole ownership of the household land, and d) individuals having managerial control over farm-related decision-making.

Decision-making power at home: Our results suggest that land ownership at the household level is associated with more decision-making power at home for older men. With most land in India being inherited through the male lineage, older men often control land and have substantial decision-making power at home. Their power is absolute and not contingent on whether their names are listed on the land title or whether they play an important operational role in farm management.

For older women, living in landed households does not necessarily mean greater decision-making power at home. Older women have power only when their land ownership is documented through land titling or operational control of the land. Ironically, older women who live in landed households but do not have their names on the land title appear to be the most disadvantaged. They have even less say in household decisions than those living in landless households.

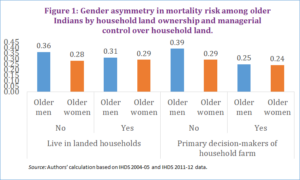

Mortality: Living in landed households is associated with a lower likelihood of dying between two waves of the survey for older men, but not for older women. Older women residing in landed households tend to face a marginally higher risk of mortality than those residing in landless households (Figure 1). However, for both older men and women, being the primary decision-makers in household farms have lower odds of mortality than those who are not.

Although it is evident that owning key household assets brings older people more bargaining power at home and greater well-being, we have found the existence of gender asymmetry in this relationship. Households owning agricultural land are associated with granting greater accord and respect to older men but not to older women. The entrenched gender inequality limits older women’s ability to crystalize this power.

The women’s movement in India has lobbied extensively to ensure that wives and daughters are considered at par with husbands and sons in land inheritance.

Our findings suggest that granting older women legal land rights is a welcome step, but not sufficient to increase their bargaining power at home. The formal recognition and exercise of this power by registering the land under women’s names and letting women exercise their control over the land are also important.

Highlights:

References

Agarwal, B. (1994). A field of one’s own: Gender and land rights in South Asia. Cambridge University Press.

Agarwal, B. (1998). Widows versus Daughters or Widows as Daughters? Property, Land, and Economic Security in Rural India. Modern Asian Studies, 32(1), 1–48.

Dharmalingam, A. (1994). Old Age Support: Expectations and Experiences in a South Indian Village. Population Studies, 48(1), 5–19.

Lee, S.-H., & Mason, A. (2012). The economic lifecycle and support systems in Asia. In D. Park, S.-H. Lee, & A. Mason (Eds.), Aging, Economic Growth, and Old-Age Security in Asia (pp. 130–160). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Sudha, S., Irudaya Rajan, S., & Sarma, P. S. (2004). Intergenerational family support for older men and women in South India. Indian Journal of Gerontology, 18(3–4), 449–465.

Yan, H.X., Desai, S., & Barik, D. Gender and Generation: Land Ownership and Older Indians’ Autonomy. Feminist Economics. Forthcoming.

****************************************************

Hope Xu Yan is a Ph.D. Candidate in Sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her research interests include social inequalities in health and well-being and parenting, children, and families. She has conducted research on the U.S., India, and China.

Sonalde Desai is a Distinguished University Professor at the University of Maryland, and Professor at NCAER and Director of NCAER’s National Data Innovation Centre. She is a demographer whose work deals primarily with social inequalities in developing countries with a particular focus on gender and class inequalities in human development. While much of her research focuses on South Asia, she has also engaged in comparative studies across Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa. She has published articles in a wide range of sociological and demographic journals including American Sociological Review, Demography, Population and Development Review, and Feminist Studies. Dr Desai leads the India Human Development Survey and is serving as President for the Population Association of America for 2022.

Debasis Barik is a Fellow at NCAER. His research revolves around issues on public health, demography, migration, gender, labor and social security. Debasis holds a PhD in Demography from International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai. He is an active member of various national and international organizations, working in areas of demography and social sciences. He has published his research on a number of reputed journals including World Development, Health Economics, etc. He has been serving as Associate Editor and Review Editor in some reputed international journals.