Adolescence, that period from approximately age 10 to 24 years of age, is a time of enormous change in young people’s brain development and cognition, family and social relationships, and social roles and expectations (Sawyer et al., 2018). It is during this period that youth in most cultures move away from authority figures, such as parents, teachers, or religious leaders, and toward peers as their primary influencers. This is also the period in which they increase their independence and agency (Bandura, 2006), but too often, girls are given less opportunity than boys to be agentic and independent.

Agency, which we can define as the capacity to act with self-regulation and self-determination to achieve one’s goals, supports adolescent development and transition into responsible and healthy adulthood (Bandura, 2006). It can also help adolescents maintain stability and resilience in the face of change, increasing the likelihood of their retention in school, economic opportunity in adulthood, and healthy sexual relationships (Sawyer et al., 2018; Taukobong et al., 2016; Zimmerman et al., 2019). For this reason, agency is a goal of global adolescent programming, especially for adolescent girls, but there remains a paucity of data on how programmes improve girls’ agency, such as their decision-making, freedom of movement, social and digital connectivity, and self-efficacy or belief in their capacities to make change in their lives.

Historically, girls’ education was viewed as the primary mechanism to strengthen girls’ agency and empowerment, and to support their capabilities to achieve self-determination (Murphy & Lloyd, 2016). However, growing evidence suggests that social norms may be an even more important target for programmes designed to increase girls’ agency (Harper & Marcus, 2018). Restrictive gender social norms – i.e., the contextually and culturally-entrenched expectations of what girls can or cannot do – can constrain girls’ agency by impeding their freedom of movement, social relationships, and access to information, typically with the goal of increasing her sexual honour, marriageability, and likelihood of childbearing and motherhood. This is often rooted in a socially limited value of women and girls, defining their achievement only in the forms of being a wife and mother (Harper & Marcus, 2018), and the norms that reinforce these values begin to intensify in early adolescence and peak by late adolescence and young adulthood (Dandona et al., 2024).

Historically, girls’ education was viewed as the primary mechanism to strengthen girls’ agency and empowerment, and to support their capabilities to achieve self-determination (Murphy & Lloyd, 2016). However, growing evidence suggests that social norms may be an even more important target for programmes designed to increase girls’ agency (Harper & Marcus, 2018). Restrictive gender social norms – i.e., the contextually and culturally-entrenched expectations of what girls can or cannot do – can constrain girls’ agency by impeding their freedom of movement, social relationships, and access to information, typically with the goal of increasing her sexual honour, marriageability, and likelihood of childbearing and motherhood. This is often rooted in a socially limited value of women and girls, defining their achievement only in the forms of being a wife and mother (Harper & Marcus, 2018), and the norms that reinforce these values begin to intensify in early adolescence and peak by late adolescence and young adulthood (Dandona et al., 2024).

India is an important context in which to consider these issues, given that one in five residents of India – almost 270 million people – are adolescents. Further, the Government of India’s Adolescent Health Strategy (IAHS) prioritises issues of gender equity and adolescents’ agency in their achievement of health, well-being, and their full potential, though there is limited guidance on how to address gender inequities in ways that improve girls’ agency (Dandona et al., 2024). The importance of addressing gender equity cannot be overstated, as restrictive gender attitudes persist strongly in the country (Pew, 2022). A recent survey conducted in India found that 87% of Indian adults believe a woman should always obey her husband, and 80% said that a man should be prioritised over a woman for a job when job access is low (Pew, 2022). Further, sex ratio imbalances disadvantaging girls, and indicative of the lower value of girls, persist, and at a notable level compared with other nations (Tafuro & Guilmoto, 2020).

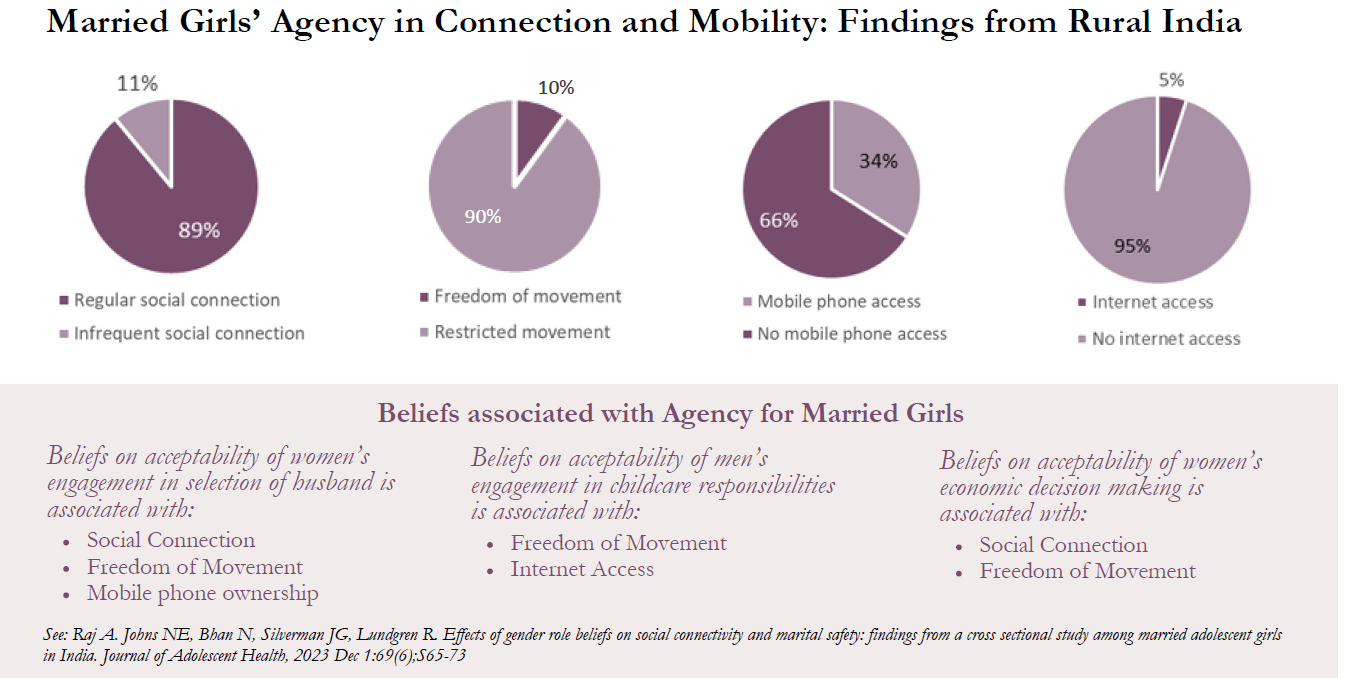

To provide further insight into the role of restrictive gender role attitudes and norms on the development of girls’ agency, our team analysed data from a cross-sectional survey conducted with married adolescent girls in rural Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in 2015 and 2016 (n=4893 15-19 year olds) (Raj et al., 2021). We examined whether traditional gender role beliefs were associated with indicators of girls’ agency. Measures on gender role beliefs included beliefs regarding appropriateness of: a) women/girls’ choice in timing for marriage, b) married women’s engagement in household economic decision-making, c) male responsibility for child needs, and d) men’s intimate partner violence against wives. Our outcome variables were freedom of movement (mobility), time with friends (social connection), and mobile phone ownership and internet access (digital connection). Findings indicate variation in effects across predictor variables.

We found that our most robust predictor of agency outcomes was holding beliefs supportive of female marital choice; this variable was associated with freedom of movement, social connection, and digital connection.(Figure 1). This finding is quite striking given that parents selected the husband in 93% of cases, and 52% of girls were not asked their opinion about this mate. Additional robust predictors were beliefs that men should be responsible to meet child needs (e.g., bathing) and beliefs that women should have economic decision-making control in households, both of which were associated with freedom of movement and digital connection. Overall, these findings suggest that gender transformative norms that support women’s decision-making control and men’s childcare responsibilities may increase women’s agency broadly in rural India, even for very young wives.

Other analyses using data with youth in India from this same study yield similar or complementary findings. Analysis of unmarried girls found that those with less traditional gender roles, using the same indicators described above, were more likely to hold career aspirations (Patel et al., 2021). Unfortunately, we did see that girls held more gender egalitarian views than did boys, which may compromise equality in heterosexual marriages in this context. A subset of married women recruited as married girls in a prior cohort of this study, collected in 1991, as well as currently married youth aged 15-21 in Jharkhand, additionally showed that those reporting that they rather than their family selected their mate were more likely to hold more gender egalitarian beliefs, and were more likely to report agency as indicated by freedom of movement, economic decision-making, and marital communication and contraceptive use (Jejeebhoy et al., 2022).

In sum, adolescence is an important time of transition and development, physically and emotionally, but restrictive gender norms and beliefs can potentially impede this development by hindering youths’ choices and capacities to act on these choices. This is especially true for girls, for whom value can be restricted to their potential roles as wife and mother, and corresponding family and community norms and resultant beliefs held by girls regarding these expectations can impede girls’ agency in decision-making, movement, and socialisation. We examined this issue using survey data from rural adolescents in two states in India and found that less restrictive gender beliefs overall are associated with greater agency for girls and reduce their risk for marital violence. Two gender beliefs in particular showed greater effects across our agency outcomes- the acceptability of girls’/women’s decision-making on the timing of marriage and the acceptability of fathers’ involvement in childcare. These findings reinforce the importance of supporting women’s decision-making related to marriage and male responsibility for domestic labour to support women and girls’ agency and safety broadly in India.

References

Bandura, A. (2006). Adolescent development from an agentic perspective. In Urdan. T. & Pajares. F. (Eds.). Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Information Age Publishing, Greenwich, Connecticut.

Dandona, R., Pandey, A., Kumar, G.A., Arora, M., & Dandona, L. (2024). Review of the India Adolescent Health Strategy in the context of disease burden among adolescents. The Lancet Regional Health-Southeast Asia. 20.

Harper, C., & Marcus, R. (2018). What can a focus on gender norms contribute to girls’ empowerment? In C. Harper, N. Jones, A. Ghimire, R. Marcus & G. Kyomuhendo Bantebya (Eds.), Empowering adolescent girls in developing countries (pp. 22-40). Routledge.

Jejeebhoy, S. J., & Raushan, M. R. (2022). Marriage without meaningful consent and compromised agency in married life: Evidence from married girls in Jharkhand, India. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(3), S78-S85.

Murphy-Graham, E., & Lloyd, C. (2016). Empowering adolescent girls in developing countries: The potential role of education. Policy Futures in Education, 14(5), 556-577. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210315610257

Patel, S. K., Santhya, K. G., & Haberland, N. (2021). What shapes gender attitudes among adolescent girls and boys? Evidence from the UDAYA Longitudinal Study in India. PloS one, 16(3), e0248766.

Pew Research Center (2022). How Indians view gender roles in families and society. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2022/03/02/how-indians-view-gender-roles-in-families-and-society/

Raj, A., Johns, N.E., Bhan, N., Silverman, J.G., & Lundgren, R. (2021). Effects of gender role beliefs on social connectivity and marital safety: Findings from a cross-sectional study among married adolescent girls in India. Journal of Adolescent Health, 1;69(6):S65-73.

Sawyer, S.M., Azzopardi, P.S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G.C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 1;2(3):223-8.

Tafuro, S., & Guilmoto, C.Z. (2020). Skewed sex ratios at birth: A review of global trends. Early Human Development. 1;141:104868.

Taukobong, H.F., Kincaid, M.M., Levy, J.K., Bloom, S.S., Platt, J.L., Henry, S.K., Darmstadt, G,L. (2016). Does addressing gender inequalities and empowering women and girls improve health and development programme outcomes? Health Policy and Planning. Dec 1;31(10):1492-514.

Youth in India (2022). Social Statistics Division, National Statistical Office, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Government of India. Youth_in_India_2022.pdf (mospi.gov.in)

Zimmerman, L. A., Li, M., Moreau, C., Wilopo, S., & Blum, R. (2019). Measuring agency as a dimension of empowerment among young adolescents globally; findings from the Global Early Adolescent Study. SSM-population health, 8.

__________________________

Anita Raj is the Executive Director of Newcomb Institute, a research and training institute at Tulane University focused on gender equity. She is also a Professor and the Nancy Reeves Dreux Endowed Chair in the Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. Her work focuses on gender equity, society, and health.

![]()