Adolescence is a stage in the life course when one begins to imagine and then prepare for adulthood. Although adolescents continue to rely on their parents for guidance and support, they begin to achieve greater independence, with widened opportunities to explore the world around them.

Adolescence is a stage in the life course when one begins to imagine and then prepare for adulthood. Although adolescents continue to rely on their parents for guidance and support, they begin to achieve greater independence, with widened opportunities to explore the world around them.

At the same time, the journey through adolescence is gendered. It is common for girls and boys to be treated as essentially different, with girls viewed as innately nurturing and boys as naturally competitive. These beliefs tend to produce their intended result, steering girls towards motherhood and domesticity and boys towards the world of paid work. To the extent that boys are seen as more valuable than girls, diverting resources such as education and health care away from girls and towards boys comes to be seen as desirable and even normative (Dube, 1988).

At the same time, the journey through adolescence is gendered. It is common for girls and boys to be treated as essentially different, with girls viewed as innately nurturing and boys as naturally competitive. These beliefs tend to produce their intended result, steering girls towards motherhood and domesticity and boys towards the world of paid work. To the extent that boys are seen as more valuable than girls, diverting resources such as education and health care away from girls and towards boys comes to be seen as desirable and even normative (Dube, 1988).

It is in the family setting that children first become aware of their own gender, start to appreciate the different expectations for behaviour placed on boys and girls, and ultimately internalise a gender identity (Endendijk et al., 2018). Parents function as active socialisation agents, differentially shaping how boys and girls approach education, mobility, leisure activities, domestic responsibilities, and more (Dittman et al., 2023). For example, researchers in India find adolescent girls are given few opportunities to venture outside the home, even as boys are largely free to involve themselves in community activities (Basu et al., 2017; Vikram et al., 2024). Parents also model behaviours that reinforce gender roles. Children observe that domestic chores are performed by mothers and that their fathers are decision-makers in the household. Consequently, girls in India learn that their proper place is in the home, fulfilling domestic duties and attending to the needs of men, whereas boys come to believe that men are superior to women and must exercise authority over them.

What is the situation for adolescents in India, a country characterised by high levels of gender inequality? Specifically, to what extent do families treat adolescents differently on the basis of their sex? Are adolescent girls more likely than adolescent boys to be aware of gender unequal treatment in the home? Finally, to what extent are gender unequal experiences in the family differentially associated with the mental health of male and female adolescents?

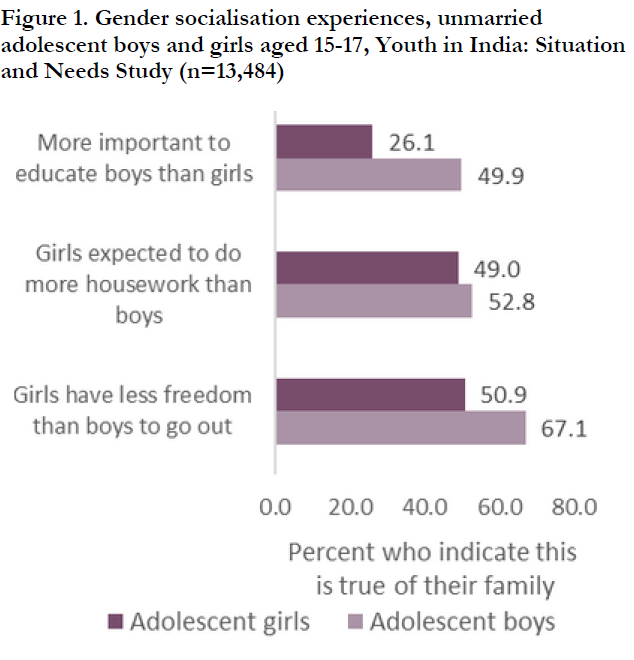

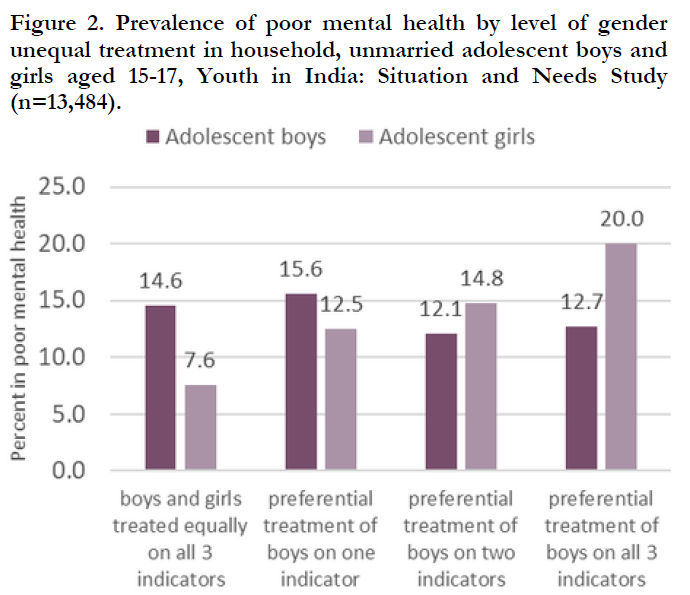

The Youth in India: Situation and Needs Study, conducted in six Indian states between 2006 and 2008, sheds some light on these questions. The current analysis is restricted to 13,484 unmarried adolescents (ages 15 to 17). The survey asked respondents three questions about their perceived treatment as a boy or girl in the household. Girls were asked “Was your education given less importance compared to your brothers”, “Were you given much less freedom to roam around or go out compared to your brothers?” and “Were you expected to do a lot more housework compared to your brothers?”. The questions were phrased the other way for male adolescents (e.g., “Was your education given more importance compared to your sisters?”). Respondents who did not have siblings of the other sex were asked to compare to cousins. For both sexes, responses indicating privileged treatment of boys were coded 1 and 0 otherwise. Items were analysed separately, but also summed to produce a scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher values representing greater preferential treatment of boys. Poor mental health was assessed with the GHQ-12, a twelve-item checklist used to screen for mental health problems in the general population. Items included whether, in the past month, respondents experienced emotions such as feeling worthless, unable to concentrate, feeling constantly under strain, and unable to enjoy normal activities. Items were coded 1 if respondents had experienced a negative emotion and 0 otherwise, then summed to produce a count of negative emotions ranging from 0 to 12. Respondents who reported three or more negative emotions in the past month were coded as having poor mental health.

The Youth in India: Situation and Needs Study, conducted in six Indian states between 2006 and 2008, sheds some light on these questions. The current analysis is restricted to 13,484 unmarried adolescents (ages 15 to 17). The survey asked respondents three questions about their perceived treatment as a boy or girl in the household. Girls were asked “Was your education given less importance compared to your brothers”, “Were you given much less freedom to roam around or go out compared to your brothers?” and “Were you expected to do a lot more housework compared to your brothers?”. The questions were phrased the other way for male adolescents (e.g., “Was your education given more importance compared to your sisters?”). Respondents who did not have siblings of the other sex were asked to compare to cousins. For both sexes, responses indicating privileged treatment of boys were coded 1 and 0 otherwise. Items were analysed separately, but also summed to produce a scale ranging from 0 to 3, with higher values representing greater preferential treatment of boys. Poor mental health was assessed with the GHQ-12, a twelve-item checklist used to screen for mental health problems in the general population. Items included whether, in the past month, respondents experienced emotions such as feeling worthless, unable to concentrate, feeling constantly under strain, and unable to enjoy normal activities. Items were coded 1 if respondents had experienced a negative emotion and 0 otherwise, then summed to produce a count of negative emotions ranging from 0 to 12. Respondents who reported three or more negative emotions in the past month were coded as having poor mental health.

Figure 1 confirms that the preferential treatment of boys in families is common. For every indicator, however, adolescent boys were more likely than were adolescent girls to identify gender unequal treatment in their home. The gender gap was greatest for those who said their families treated education as more important for boys than girls, with half as many girls as boys indicating this was true for their families (26.1% versus 49.9%).

Figure 1 confirms that the preferential treatment of boys in families is common. For every indicator, however, adolescent boys were more likely than were adolescent girls to identify gender unequal treatment in their home. The gender gap was greatest for those who said their families treated education as more important for boys than girls, with half as many girls as boys indicating this was true for their families (26.1% versus 49.9%).

Interestingly, the association between gender unequal treatment and poor mental health operated differently for adolescent girls than it did for adolescent boys (Figure 2). Adolescent girls reported correspondingly worse mental health as the preferential treatment of boys in their families increased. In contrast, adolescent boys’ perceptions of gender unequal treatment were unrelated to their mental health. The resulting pattern was that when families treated males and females equally, nearly half as many adolescent girls as adolescent boys reported poor mental health (7.6% versus 14.6%). When boys were treated better than girls across all three indicators, mental health trended in the other direction, with more adolescent girls than boys in poor mental health (20.0% versus 12.7%).

These results, also discussed in Ram et al. (2014), provide a small window into the gender socialisation of Indian adolescents. Yet, there is much more to do. Today, these respondents are in their thirties and most, if not all, are themselves parents. As their children enter adolescence, will they also perceive gender unequal treatment in their families? Will the people that they ultimately become depend on their talents and aspirations, or, as historically been the case in India, what is deemed appropriate for their gender?

These results, also discussed in Ram et al. (2014), provide a small window into the gender socialisation of Indian adolescents. Yet, there is much more to do. Today, these respondents are in their thirties and most, if not all, are themselves parents. As their children enter adolescence, will they also perceive gender unequal treatment in their families? Will the people that they ultimately become depend on their talents and aspirations, or, as historically been the case in India, what is deemed appropriate for their gender?

References

Basu, S., Zuo, X., Lou, C., Acharya, R., & Lundgren, R. (2017). Learning to be gendered: Gender socialization in early adolescence among urban poor in Delhi, India, and Shanghai, China. Journal of Adolescent Health 61: S24–S29.

Dittman, C.K., Sprajcer, M. & Turley, E.L. (2023). Revisiting gendered parenting of adolescents: Understanding its effects on psychosocial development. Current Psychology 42, 24569–24581.

Dube, L. (1988). On the construction of gender: Hindu girls in patrilineal India. Economic and Political Weekly 23(18), WS11-WS19.

Endendijk, J.J., Groeneveld, M.G. & Mesman, J. (2018). The gendered family process model: An integrative framework of gender in the family. Archives of Sexual Behavior 47, 877–904.

Ram, U., Strohschein, L., & Gaur, K. (2014). Gender socialization: Differences between male and female youth in India and associations with mental health. International Journal of Population Research. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/357145

Vikram, K., Ganguly, D., & Goli, S. (2024). Time use patterns and household adversities: A lens to understand the construction of gender privilege among children and adolescents in India. Social Science Research 118, 102970.

_______________________

Lisa Strohschein is Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Alberta. Her work involves investigating how family dynamics influence development and well-being. She was president of the Canadian Population Society from 2019-2022 and is currently serving as Editor-in-Chief for its flagship journal, Canadian Studies in Population.

![]()