Adolescence is an important window where gender roles and norms interplay with the onset of puberty and start solidifying (Amin, 2018; Lundgren, 2013). Studies have shown that during early adolescence (10-14 years) both girls and boys are faced with increased expectations to follow unequal gender norms (McCarthy, 2016). Gender norms formed during early adolescence often influence health and sexuality in later adolescence and beyond. Gender inequalities, such as stereotypical gender attitudes, men’s authority over women, and unequal access to resources, are associated with negative health outcomes, gender-based violence, and economic vulnerability (Heise et al., 2015; Peacock & Barker, 2014). Gender socialisation, the process of teaching/learning about being a girl or a boy, starts as early as birth and extends throughout adolescence (Hill & Lynch, 1983). It includes teaching girls to be prepared for the roles of wife and mother and training boys to shoulder the roles of provider and protector (Giddens, 2006; ICRW, 2010; Lundgren, 2015).

Appropriate behaviours for males and females are learned and internalised through exposure to different socialising agents such as family, media, and social institutions (Giddens, 2006; Lou et al., 2012). However, children do not passively absorb and embody social messages; they interact with others to produce their own form of gender identity. Gender is an acquired identity that is learned, changes over time, and varies widely within and across cultural contexts.

In this paper we specifically tried to understand (1) what gender norms are transmitted to boys and girls and by whom; (2) how these norms are transmitted and whether this process differs by sex; and (3) what differences and similarities in gender socialisation are manifested in urban settings in two Asian countries with diverse cultural, political, and economic contexts. About three-fifths (58%) of early adolescents (10-14 years) reside in China and India. No other studies have compared India and China that have similarities in terms of population and gender disparity in terms of son preference and skewed sex ratio at birth.

In this paper we specifically tried to understand (1) what gender norms are transmitted to boys and girls and by whom; (2) how these norms are transmitted and whether this process differs by sex; and (3) what differences and similarities in gender socialisation are manifested in urban settings in two Asian countries with diverse cultural, political, and economic contexts. About three-fifths (58%) of early adolescents (10-14 years) reside in China and India. No other studies have compared India and China that have similarities in terms of population and gender disparity in terms of son preference and skewed sex ratio at birth.

Methodology

The study was located in two disadvantaged urban communities in Delhi, India and Shanghai, China and was part of the multi-country (15) Global Early Adolescent Study. Qualitative methodologies were used with boys and girls aged 11–13 years, including 16 group-based timeline exercises and 65 narrative interviews. In addition, 58 parents of participating adolescents were interviewed. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, translated, and uploaded into Atlas.ti for coding and thematic analysis.

Findings

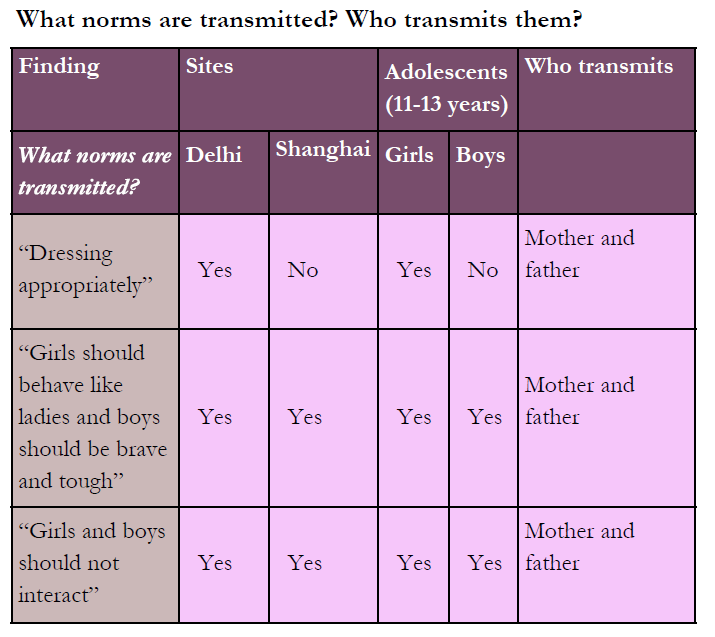

Boys and girls growing up in the same community were directed onto different pathways during their transition from early to late adolescence. Adolescents and parents in both sites identified mothers as the primary actor, socialising adolescents into how to dress and behave and what gender roles to play, although fathers were also mentioned as influential. Opposite-sex interactions were restricted, and violations enforced by physical violence.

Boys and girls growing up in the same community were directed onto different pathways during their transition from early to late adolescence. Adolescents and parents in both sites identified mothers as the primary actor, socialising adolescents into how to dress and behave and what gender roles to play, although fathers were also mentioned as influential. Opposite-sex interactions were restricted, and violations enforced by physical violence.

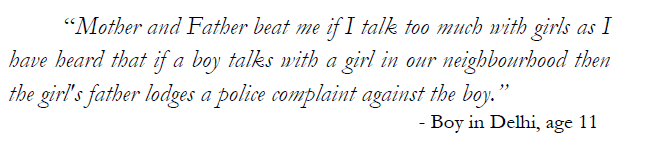

In Delhi, gender roles and mobility were more strictly enforced for girls than boys. Restrictions on opposite-sex interactions were rigid for both boys and girls in Delhi and Shanghai. Sanctions, including beating, for violating norms about boy-girl relationships were more punitive than those related to dress and demeanour, especially in Delhi. Education and career expectations were notably more equitable in Shanghai.

Gender socialisation Process

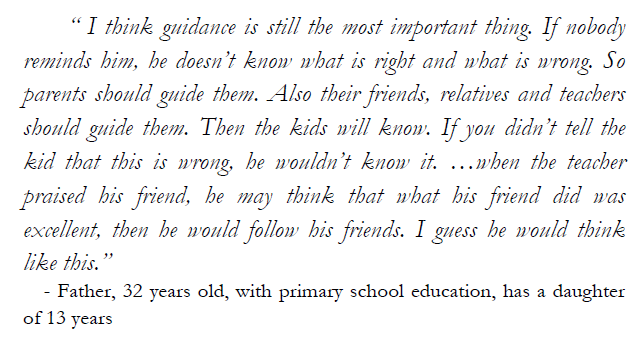

Overall, in Delhi and Shanghai, adolescents and their parents identified mothers as the most important actor in the socialisation process, although fathers were mentioned as well—especially in relationship to boys. They also discussed the influence of teachers, as well as siblings, extended families and peers, although in a more limited role than parents. The primary processes of socialisation referred to were instruction, encouragement, and positive reinforcement. Scolding, punishment such as shaming in front of peers, and beating by parents and teachers were cited by boys and girls in Shanghai.

Adolescents and adults in both settings reported that beating and scolding were often used to enforce norms, especially those related to boy/girl relationships. Physical punishment was more marked in Delhi and more commonly used with boys than girls.

Adolescents and adults in both settings reported that beating and scolding were often used to enforce norms, especially those related to boy/girl relationships. Physical punishment was more marked in Delhi and more commonly used with boys than girls.

From the perspective of teachers and parents, imitation of others, especially peers and media characters who conformed to stereotyped gender identities, was instrumental in the socialisation process. In both settings, but especially in Shanghai, parents expressed concerns that media (romantic soaps) influenced the interaction between boys and girls in Shanghai.

Discussion

This study shows that despite significant modernisation underway in both India and China, entrenched gender inequities flowing from dominant patriarchal structures persist, with potential long-term negative outcomes for adolescents. The results illustrate the interplay between the efforts of parents (Kågesten et al., 2016) to inculcate traditional values and norms, such as those related to purity and modesty, and the influence of structural transformations bringing expanded economic roles for women. Increased understanding of this dynamic process provides insight into opportunities to increase gender equality. Children learn about gender by watching and imitating those around them and through explicit instruction, discipline, and sanctions (Vikram et al., 2024). Thus, it is important to work with parents and communities, as well as with the children themselves, to foster critical reflection of the negative consequences of gender inequity and offer alternative ways of performing masculine and feminine roles. Efforts to bring about more equitable gender norms would lay a foundation for improved health and well-being over the life course (McCarthy et al., 2016). Such programs have been limited in number, scale and impact. Information from longitudinal studies on gender socialisation across different cultural settings would inform the design of gender transformative programming.

References

Amin, A., Kågesten, A., Adebayo, E., & Chandra-Mouli, V. (2018). Addressing gender socialization and masculinity norms among adolescent boys: policy and programmatic implications. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(3), S3-S5.

Giddens, A. (2006). Sociology. 5th edition. Cambridge: Polity Press;392.

Heise, L. L., & Kotsadam, A. (2015). Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: an analysis of data from population-based surveys. The Lancet Global Health, 3(6), e332-e340.

Hill, J., & Lynch, M. (1983). The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen A. (eds.), Girls at puberty: Biological and psychosocial perspectives. New York: Plenum Springer US; 1983:201e28.

International Centre for Research on Women (ICRW). (2010). The Girl Effect: What do boys have to do with it? Briefing note for an Expert Meeting and Workshop. Washington, DC, 5e6 October.

Kågesten, A., Gibbs, S., Blum, R. W., Moreau, C., Chandra-Mouli, V., Herbert, A., & Amin, A. (2016). Understanding factors that shape gender attitudes in early adolescence globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PloS one, 11(6), e0157805.

Lou, C., Cheng, Y., & Gao, E. (2012). Media’s contribution to sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors for adolescents and young adults in three Asian cities. J Adolesc Health, 50:S26e36.

Lundgren, R. (2015). The cultural ecology of youth and gender-based violence in Northern Uganda. Digital Repository at the University of Maryland.. http://dx.doi.org/10.13016/M2QC9C. Accessed May 30, 2017

Lundgren, R., Beckman, M., Chaurasiya, S. P., Subhedi, B., & Kerner, B. (2013). Whose turn to do the dishes? Transforming gender attitudes and behaviours among very young adolescents in Nepal. Gender & Development, 21(1), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2013.767520

McCarthy, K., Brady, M., & Hallman, K. (2016). Investing when it counts: Reviewing the evidence and charting a course of research and action for very young adolescents. New York: Population council.

Peacock, D., & Barker, G. (2014). Working with men and boys to prevent gender-based violence: Principles, lessons learned, and ways forward. Men Masc; 17:578e99.

Vikram, K., Ganguly, D., & Goli, S. (2024). Time use patterns and household adversities: A lens to understand the construction of gender privilege among children and adolescents in India. Social Science Research, 118, 102970.

_________________________

Sharmishtha Basu has more than 17 years experience in a wide range of global health, nutrition, and bringing evidence to policy. She has led large-scale, multi-country nutrition and health programmes and managed several qualitative and quantitative research projects within and outside India. Currently, Dr. Basu provides technical assistance to the Ministry of Women and Child Development, GOI and also supports a Data2Policy project in Eschborn, Germany. She has a PhD in Population Studies from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

![]()