The experiences of older women and elder widows are often hidden and their voices are muted in the literature of South Asia and India. Gender scholarship has predominantly centred on women during their reproductive years as wives and mothers, often overlooking the broader spectrum of their experiences beyond these roles. This oversight may stem from the notion that gender loses its critical significance as women age. Even as gender roles and norms may relax for women as they age, the enduring impact of accumulated discrimination and intersectional experiences tied to gender, age and widowhood persists and continues to shape their experiences in later life.

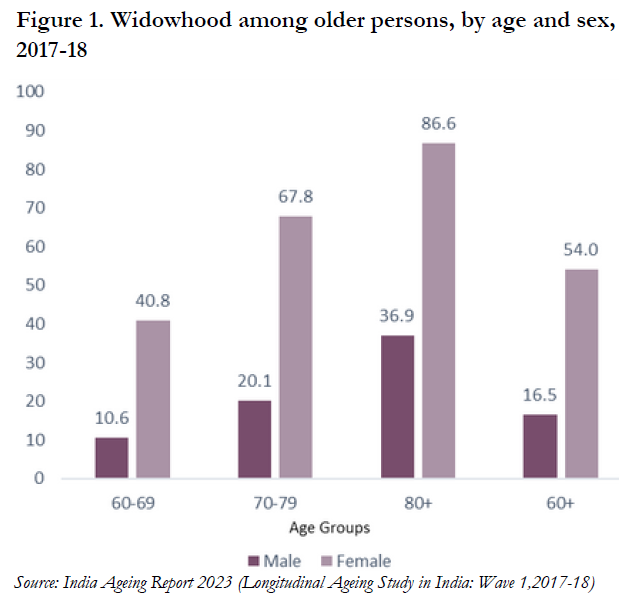

India, considered a young country, is experiencing a demographic shift with the number of people over the age of 60 expected to double by 2050, comprising 21% of the total population (IIPS & UNFPA, 2023). With this ageing population comes an increase in the feminisation of older age groups, with a notable prevalence of widowhood among aged women. Nearly 54 per cent of all aged (60 years and older) women in India are widowed compared with only 16 per cent of men. The percentage of widows increases from just 40.8 per cent among the 60-69 age group to 86.6 per cent among women of the 80+ age group (Figure 1). Higher female life expectancy at ages 60 and 70, the universal tendency for women to marry men older than them and the social restrictions on widows to remarry have led to the high incidence of widowhood among females at higher ages.

India, considered a young country, is experiencing a demographic shift with the number of people over the age of 60 expected to double by 2050, comprising 21% of the total population (IIPS & UNFPA, 2023). With this ageing population comes an increase in the feminisation of older age groups, with a notable prevalence of widowhood among aged women. Nearly 54 per cent of all aged (60 years and older) women in India are widowed compared with only 16 per cent of men. The percentage of widows increases from just 40.8 per cent among the 60-69 age group to 86.6 per cent among women of the 80+ age group (Figure 1). Higher female life expectancy at ages 60 and 70, the universal tendency for women to marry men older than them and the social restrictions on widows to remarry have led to the high incidence of widowhood among females at higher ages.

Widowhood, often coinciding with old age for women, brings not only a weakening of social ties formed through marriage but also a significant decline in their social and economic status. The sharp gender disparities in access to resources, coupled with patriarchal norms that tie women’s claims on resources to marriage, render them vulnerable in widowhood. In a country where female labour force participation is low and many women rely on the family for economic support, widows face additional challenges in seeking employment due to social and ritual restrictions on their mobility and weak bargaining power in the labour market mediated by caste, age and social context (Chen 2000; Lamb 2000). Despite the significant contribution (4.3 hours a day globally) of older women and widows to unpaid domestic and care labour within households (including caring for grandchildren and other adults), their work remains invisible, unrecognised and uncompensated, and they frequently experience unmet care needs in old age (Age International, 2021). This lifetime of unpaid care labour, coupled with inadequate state-sponsored social protection for the elderly in India, renders older widows increasingly vulnerable to neglect and poverty. While some states provide old-age pensions that cover destitute elderly widows and others offer special pension schemes for widows of all ages, issues such as insufficient pension, narrow eligibility criteria, funding inadequacies and delays underscore the shortcomings in addressing the economic vulnerabilities of widows within these pension schemes (Rajan, 2001).

Widowhood, often coinciding with old age for women, brings not only a weakening of social ties formed through marriage but also a significant decline in their social and economic status. The sharp gender disparities in access to resources, coupled with patriarchal norms that tie women’s claims on resources to marriage, render them vulnerable in widowhood. In a country where female labour force participation is low and many women rely on the family for economic support, widows face additional challenges in seeking employment due to social and ritual restrictions on their mobility and weak bargaining power in the labour market mediated by caste, age and social context (Chen 2000; Lamb 2000). Despite the significant contribution (4.3 hours a day globally) of older women and widows to unpaid domestic and care labour within households (including caring for grandchildren and other adults), their work remains invisible, unrecognised and uncompensated, and they frequently experience unmet care needs in old age (Age International, 2021). This lifetime of unpaid care labour, coupled with inadequate state-sponsored social protection for the elderly in India, renders older widows increasingly vulnerable to neglect and poverty. While some states provide old-age pensions that cover destitute elderly widows and others offer special pension schemes for widows of all ages, issues such as insufficient pension, narrow eligibility criteria, funding inadequacies and delays underscore the shortcomings in addressing the economic vulnerabilities of widows within these pension schemes (Rajan, 2001).

Additionally, widowhood in India is marked by a lack of access to essential resources such as land rights. Women’s property rights, in general, tend to be weak, and the prevalent male advantage in property inheritance and control renders widows progressively more vulnerable (Agarwal, 1998). Research indicates that more extensive and secure land rights among widows could translate into other perceptible benefits such as a higher likelihood of co-residence with children, lower vulnerability to intra-household discrimination, and an independent source of income (Dreze, 1990). Despite the existing legal provisions, limited land rights and lack of effective control of the land exacerbate the economic precarity experienced by older widows.

Gender inequalities experienced throughout their lives consequently contribute to poor health outcomes in later life for women. With an increase in life expectancy, women spend more years and a larger proportion of their lives with poor health outcomes like mobility limitation compared to men (Sreerupa et al., 2018). The intersectionality of gender, widowhood, and ageing further exacerbates the health disparities experienced by older widows. Research indicates that older widows are disproportionately affected by poor health outcomes, particularly chronic health conditions (Agrawal and Keshri, 2014), yet they are less likely to seek healthcare services and often spend less when they do (Sreerupa and Rajan, 2010). This lower utilisation and spending on healthcare services among older widows underscores broader systemic failures in addressing the healthcare needs of marginalised populations, particularly elderly widows.

To advance a more equitable and inclusive society for all ages, it is imperative to recognise and amplify the experiences and voices of older women and widows in the discourse shaping public policy, programme design and shift in gender norms. Addressing the intersecting challenges faced by older women and widows in India is not only crucial for achieving SDG 5 on gender equality but also aligns with the broader commitment of the 2030 Agenda to “leave no one behind.”

References

Age International (2021), Older women: the hidden workforce. https://www.ageinternational.org.uk/globalassets/documents/reports/2021/age-international-older-women-report-v11-final-spreads.pdf

Agarwal, B. (1998). Widows versus daughters or widows as daughters? Property, land and economic security in rural India. In M. A. Chen (Ed.), Widows in India: Social neglect and public action (pp. 124–169). New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Agrawal, G., & Keshri, K. (2014). Morbidity Patterns and Health Care Seeking Behavior among Older Widows in India. PLoS ONE, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094295

Chen, M. 2000. Perpetual Mourning: Widowhood in Rural India. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Dreze, J. (1990). Widows in rural India. STICERD DEP No. 26. London: London School of Economics

International Institute for Population Sciences & United Nations Population Fund (2023). India Ageing Report 2023, Caring for Our Elders: Institutional Responses. United Nations Population Fund, New Delhi.

Rajan, S. I. (2001). Social assistance for poor elderly: How effective? Economic and Political Weekly. 36, 613–617

Lamb, S. (2000). White saris and sweet mangoes: Aging, gender, and body in north India. Los Angeles: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520935266

Sreerupa, & S. I. Rajan (2010) Gender and Widowhood: Disparity in Health Status and Health Care Utilization Among the Aged in India, Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 19:4, 287-304, DOI: 10.1080/15313204.2010.523650

Sreerupa, S. I. Rajan, A. Shweta, Y. Saito, & R. Malhotra (2018). Living longer: For better or worse? Changes in life expectancy with and without mobility limitation among older persons in India between 1995–1996 and 2004. International Journal of Population Studies, 4(2), 23-34.

_____________________________

Dr. Sreerupa is a Research Fellow and Program Lead at ISST, with prior role as a postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Women’s Development Studies and King’s College London. Her research expertise lies in gender, unpaid and paid care work, ageing, migration and health. She has contributed to numerous national and international books and journals.