It is a truism that time is a gendered resource. Men and women allocate their time to different activities that are socially and culturally determined. This is further complicated in later life when individuals experience life-course transitions. With a growing older population around the globe, countries (including India) are facing challenges to maintain the good physical and mental health of their ageing populations. Most importantly, how changes in age and gender intersect with everyday living, particularly the time-use of older individuals, remains unexplored in the Indian context. Along with this demographic transition, population ageing is further complicated by related changes experienced by these older individuals. For instance, technological and medical innovations, changing physical and mental health, and broader changes in our societies have altered the nature of everyday living, where we see a growing number of older adults who are experiencing improved health and economic stability; but it is entangled with cultural factors like growing market economy that caters specifically to older adults and neoliberal health policies, amongst many other changes of our societies. More recently, the latter changes have resulted in a growing population of active and healthy agers, who are successfully ageing. This changing rhetoric re-defines growing old as independent and active individuals who productively and actively engage with their time (Lamb, 2020; Samanta, 2018).

The recent release of the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (henceforth LASI, Wave-I, 2017-2018) allows us to explore certain questions on gendered time-use patterns among older adults. More specifically, the longitudinal nature of the dataset allows us to study if these time allocation patterns become less gendered as individuals experience transitions from paid work to retirement. In fact, as the meaning of time and its productive use might be re-defined with age, temporal explorations of ageing hold insights into later life well-being (Sayer et al., 2016) and subjective experiences of ageing (Twigg and Martin, 2015). This dataset marks an important onset of producing data on older adults, aged 45 and above, that has aimed to explore the physical, mental, and social well-being of the ageing population. It also holds a few experimental modules, one of which provides information on their everyday time allocation. Shifting the gaze from biomedical health concerns, this piece looks into the everyday activities of these individuals, re-defining growing old in present-day India. Moreover, using time stamps for different activities, the temporal lens allows us to see the deeper structures of our societies, that is, the underlying structures of cultural beliefs, power structures, and individual behaviours.

The recent release of the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (henceforth LASI, Wave-I, 2017-2018) allows us to explore certain questions on gendered time-use patterns among older adults. More specifically, the longitudinal nature of the dataset allows us to study if these time allocation patterns become less gendered as individuals experience transitions from paid work to retirement. In fact, as the meaning of time and its productive use might be re-defined with age, temporal explorations of ageing hold insights into later life well-being (Sayer et al., 2016) and subjective experiences of ageing (Twigg and Martin, 2015). This dataset marks an important onset of producing data on older adults, aged 45 and above, that has aimed to explore the physical, mental, and social well-being of the ageing population. It also holds a few experimental modules, one of which provides information on their everyday time allocation. Shifting the gaze from biomedical health concerns, this piece looks into the everyday activities of these individuals, re-defining growing old in present-day India. Moreover, using time stamps for different activities, the temporal lens allows us to see the deeper structures of our societies, that is, the underlying structures of cultural beliefs, power structures, and individual behaviours.

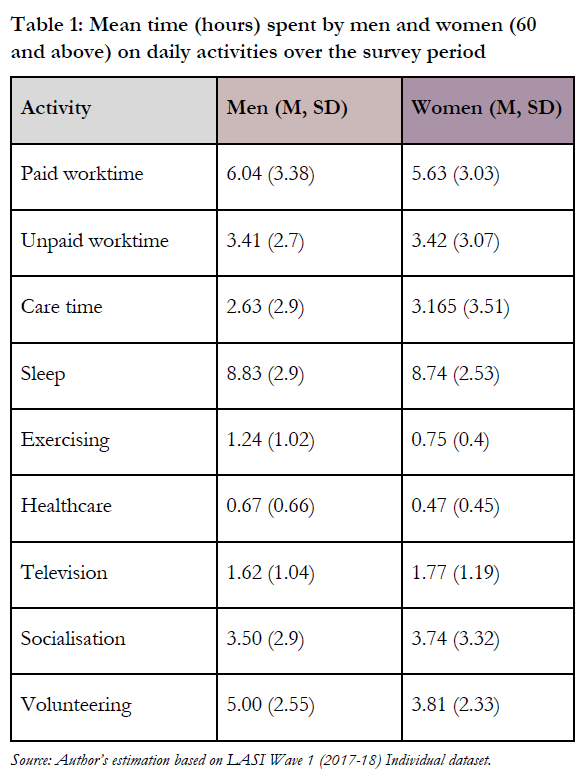

Of the 66,606 individuals aged 45 and above in the LASI dataset, the analytical sample for this paper comprises 31,902 older individuals aged 60 and above. Nearly 30% of these older adults continue to work as paid labourers, along with caring for family members including their grandchildren. Although work time reduces in later life for men, many older men and women with depressed savings, pension, and social security income continue to be employed during their retirement years (Chattopadhyay et al., 2022). The stylised questions have collected detailed time spent on different activities, as presented in Table 1.

If we look at the difference between older men and women and how much time they spend on different activities, there are no stark differences in the mean daily hours. However, these numbers need to be studied in the light of macro-level characteristics (like education, employment, and family structure) that influence individuals’ decisions about time allocations. Moreover, men of all ages report higher work and leisure than women, thus resulting in continued gender differences in later life. This seems to exist irrespective of transitions out of employment and other life-course roles. Similar findings have been recorded in developed countries as well (Calasanti et al., 2021; Gautheir and Smeeding, 2010), where gender difference that took root in early life continue in later life. The differences in paid and unpaid work are modest, which could also be due to the low levels of time captured by stylised data. Stylised time-use questionnaires are cognitively more demanding than other methods of data collection (Hirway, 2010). This can be studied in more detail as one explores the nature of work performed in paid and unpaid categories (i.e., if it is waged or not, self-employed or seasonal). Also, the stylised method relies on a broadly shared meaning of the activity (Sayer et al., 2016) and, therefore, overlooks the subjective understanding of everyday activities.

If we look at the difference between older men and women and how much time they spend on different activities, there are no stark differences in the mean daily hours. However, these numbers need to be studied in the light of macro-level characteristics (like education, employment, and family structure) that influence individuals’ decisions about time allocations. Moreover, men of all ages report higher work and leisure than women, thus resulting in continued gender differences in later life. This seems to exist irrespective of transitions out of employment and other life-course roles. Similar findings have been recorded in developed countries as well (Calasanti et al., 2021; Gautheir and Smeeding, 2010), where gender difference that took root in early life continue in later life. The differences in paid and unpaid work are modest, which could also be due to the low levels of time captured by stylised data. Stylised time-use questionnaires are cognitively more demanding than other methods of data collection (Hirway, 2010). This can be studied in more detail as one explores the nature of work performed in paid and unpaid categories (i.e., if it is waged or not, self-employed or seasonal). Also, the stylised method relies on a broadly shared meaning of the activity (Sayer et al., 2016) and, therefore, overlooks the subjective understanding of everyday activities.

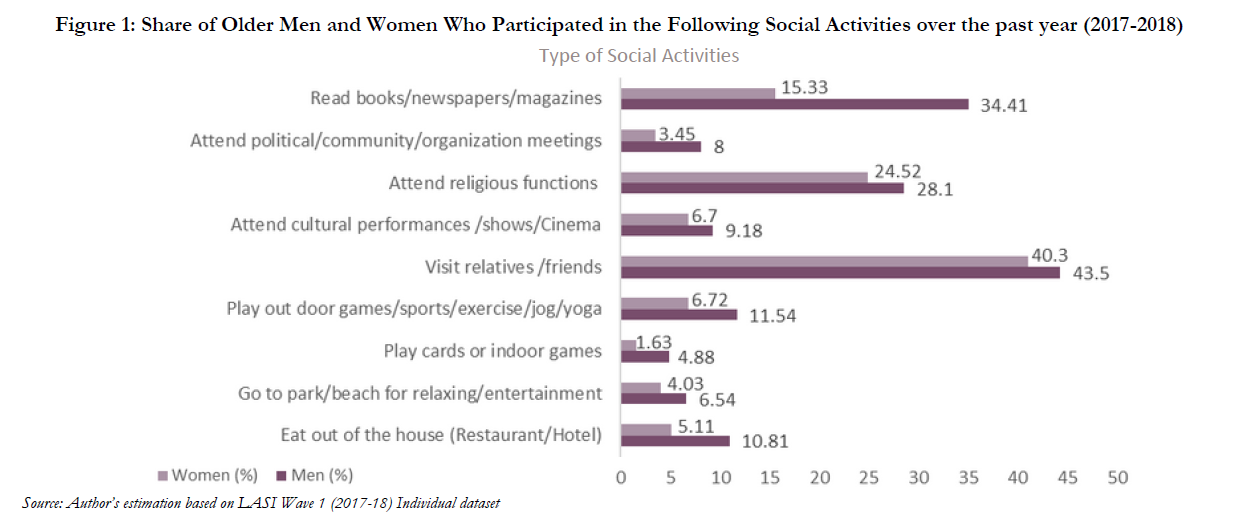

Taking a life-course perspective, women’s time is expected to shift as family roles evolve, while some changes and continuity are expected in time-use patterns. For instance, it is expected for women that as their children transition into adults there will be decreased care-giving responsibilities and increased time for self-care. This also depends on their formal labour engagements, grandchildren’s responsibilities and their leisure engagements. In Figure 1, the participation rates of men and women from LASI show substantial differences. At a micro level, the findings show men were more actively participating in leisure activities than women. However, the very nature of leisure activities also differentiates everyday participation. For instance, older Indian men were seen to engage in more passive forms of leisure (like reading or watching television), while women preferred social leisure like meeting friends (for details, see Tripathi and Samanta, 2023). At a macro level, access to leisure activities and area of residence (urban/rural) were important factors for leisure engagements. Overall, leisure has been extensively linked to psychological and physical well-being (Stebbins, 2018) across age groups and, with recent emphasis on successful and active ageing, leisure has been recognised for healthy ageing and self-managing numerous health conditions experienced by older adults. This allows for alternative discussions around ageing that are not solely focused on dependency, frailty and family support for older Indian adults. For this, time-use studies not only allow us to look at the differential allocation of time between women and men across the life-course but also its relationships with economic, social and other resources.

References

Calasanti, T., Carr, D., Homan, P. and Coan, V. (2021). Gender disparities in life satisfaction after retirement: the roles of leisure, family, and finances. The Gerontologist, 61(8), pp.1277-1286.

Chattopadhyay, A., Khan, J., Bloom, D. E., Sinha, D., Nayak, I., Gupta, S., Lee, J., & Perianayagam, A. (2022). Insights into labor force participation among older adults: Evidence from the longitudinal ageing study in India. Journal of Population Ageing, 15(1), 39-59.

Gauthier, A.H. and Smeeding, T.M. (2010). Historical trends in the patterns of time use of older adults. Ageing in Advanced Industrial States: Riding the Age Waves-Volume 3, 289-310.

Hirway, I. (2010). Time-Use surveys in developing countries: An assessment. In Unpaid work and the economy: Gender, time use and poverty in developing countries, Editors:Antonopouls, R. and Hirway, I (pp. 252-324). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Lamb, S. (ed.) (2019). Successful aging as a contemporary obsession: Global perspectives. Rutgers University Press.

Samanta, T. (2018). The “Good Life”: Third Age, Brand Modi and the cultural demise of old age in urban India. Anthropology & Aging, 39(1), pp.94-104.

Sayer, L.C., Freedman, V.A. and Bianchi, S.M. (2016). Gender, time use, and aging. In Handbook of aging and the social sciences (pp. 163-180). Academic Press.

Tripathi, A., & Samanta, T. (2023). “I Don’t Want to Have the Time When I Do Nothing”: Aging and Reconfigured Leisure Practices During the Pandemic. Ageing International, pp.1-22.

Twigg, J., & Martin, W. (eds.), (2015). Routledge handbook of cultural gerontology. Routledge.

_____________________________

Ashwin Tripathi is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in FLAME University. Her broad areas of interests are Sociology of Aging, Leisure Studies and Research Methods. She has been exploring the everyday blurring of productive and unproductive activities using a mixed method approach, with a particular interest in Time-Use studies.