Female migration in India has mostly been studied in terms of marriage migration, where a woman changes her place of residence to live with her husband post marriage, or migration along with her husband or family for various reasons, which could be economic, social or political. The category of migration being discussed in this paper is a relatively recent phenomenon- temporary migration of women, mostly unmarried, unaccompanied, low-skilled or semi-skilled and originating from rural regions of the North- Eastern states of India to bigger cities of India, to explore livelihood options in the booming service industry.

Female migration in India has mostly been studied in terms of marriage migration, where a woman changes her place of residence to live with her husband post marriage, or migration along with her husband or family for various reasons, which could be economic, social or political. The category of migration being discussed in this paper is a relatively recent phenomenon- temporary migration of women, mostly unmarried, unaccompanied, low-skilled or semi-skilled and originating from rural regions of the North- Eastern states of India to bigger cities of India, to explore livelihood options in the booming service industry.

The growth of the service industry, particularly in the retail and hospitality sectors, seems to be the dominant source of attraction for this strand of migration (McDuie-Ra, 2012; Remesh, 2012; Kikon & Karlsson, 2019). Within this category of migrants, young and unmarried women have a very high presence (Kikon & Karlsson, 2019; Baruah, 2022).

The growth of the service industry, particularly in the retail and hospitality sectors, seems to be the dominant source of attraction for this strand of migration (McDuie-Ra, 2012; Remesh, 2012; Kikon & Karlsson, 2019). Within this category of migrants, young and unmarried women have a very high presence (Kikon & Karlsson, 2019; Baruah, 2022).

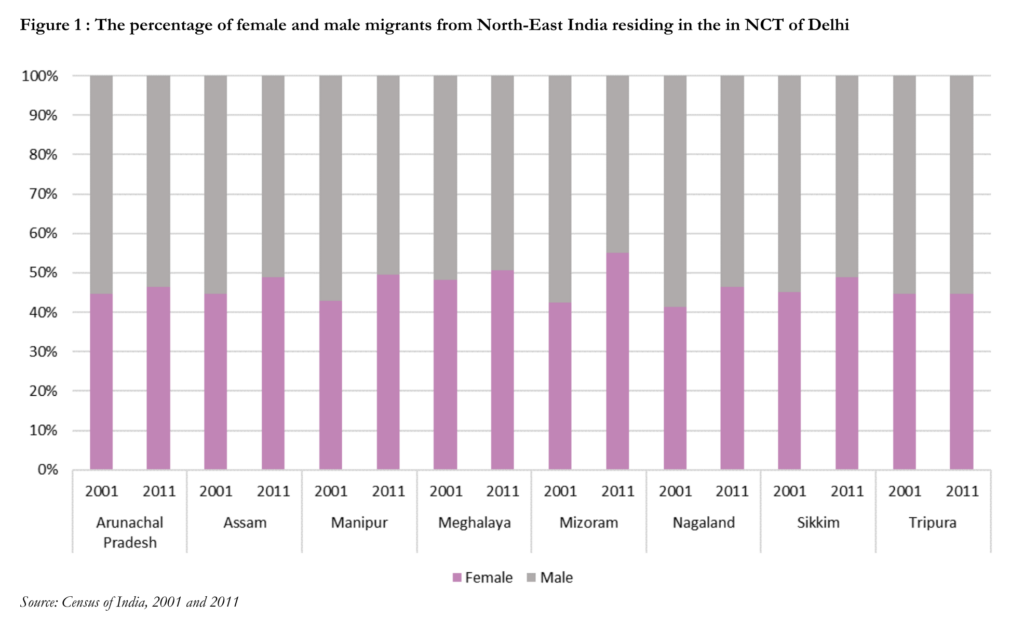

Census data for the years 2001 and 2011 show a decline of about 0.5 per cent in the share of migrant population from the North-Eastern states of India residing in the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi.

However, in terms of the male-female ratio, it is found that the proportion of female migrants, among the total migrants from North-East India, has increased from 43.9 per cent in 2001 to 48.8 per cent in 2011. As shown in Figure 1, except for the state of Tripura, the share of female migration from all the North-Eastern states has climbed up, with Mizoram showing the highest increase (from 42.6 per cent in 2001 to 49.5 per cent in 2011).

Due to their racial similarities with people from East and South-East Asia, men and women from certain regions of North-East India are seen, by employers of the retail and hospitality industries, as suitable for working in the concerned jobs to be able to put up a ‘cosmopolitan’ experience for their customers, particularly ones that work for international brands or ones that are based on East on South- East Asian themed products. Just as the décor and costumes that are usually seen inside most East or South-East Asian styled restaurants and massage parlours (e.g. Chinese restaurants, Korean restaurants, Thai spas, Japanese spas, etc.) are designed to match the cultural theme of the place, in a similar vein, workers too tend to be stylised to camouflage with the so-called cultural theme. For this purpose, migrants from North-East India tend to be the preferred pool of workers.

In the course of my doctoral research, I have also found that the migrant status adds to the feasibility of the North-East migrants to engage in these jobs. Particularly in the restaurant and spa jobs, several women who live with their families, married women, or women who have relatives living in Delhi or nearby, show reluctance towards working in these industries for the fear of being ridiculed or prejudiced by relatives for the apparent low status and sexual stereotypes associated with these jobs. Therefore, women migrants from North-East India, who are staying far from their families, opt for these jobs. Moreover, when it comes to the mobility and the working status of women, cultural norms for women in the North-Eastern societies also tend to be much more liberal as compared to other parts of India. Thus, migrant women from the North-Eastern states readily take up jobs in these sectors, and often even enjoy the moral support of their families for their work. Therefore, working in the service industry provides these women, who mostly come from a rural background and with low education, a platform to earn their livelihoods, become financially independent, provide economic support to their parents and siblings, fulfil their aspirations of living and working in the cities, and experience a symbolic form of upward social mobility through participation in high consumerist spaces like international retail showrooms, restaurants, and shopping malls.

However, due to limitations in terms of educational qualifications and skill diversity, and perceptions and experiences of discrimination in other fields of work, most of these women find their opportunities restricted to specific jobs in the service industry. As a result, the concentration of migrant women in specific job roles in restaurants/ cafes, beauty salons, massage parlours, etc. causes a reinforcement of the stereotypes that tend to sexualise and exotifies North- Eastern women.

However, due to limitations in terms of educational qualifications and skill diversity, and perceptions and experiences of discrimination in other fields of work, most of these women find their opportunities restricted to specific jobs in the service industry. As a result, the concentration of migrant women in specific job roles in restaurants/ cafes, beauty salons, massage parlours, etc. causes a reinforcement of the stereotypes that tend to sexualise and exotifies North- Eastern women.

Several studies also show that migrant women and men from North-East India have frequently faced discrimination in the national capital from landlords when they look for accommodation in the city (McDuieRa, 2012; Remesh, 2012;). Certain stereotypes were being attached to the identity of North-East migrants that make the host society perceive North-Easterners, particularly women, as ‘too outgoing’, or ‘too casual’ or ‘frequently partying types’, etc., which tend to give them the notoriety of being troublesome tenants due to which house-owners often display an unwillingness to accommodate North-East migrants or charge them with unfairly higher rents.

Therefore, it is essential to identify the needs and concerns of migrant women and also to understand that different migrant groups have differential experiences and needs. Also, the importance of skill development and skill diversification should be recognised by the government, both at the national as well as the local levels. Unless efforts are made to do away with social stigmas and social risks that are associated with certain occupations, which are providing livelihoods to a large population of women, economic and social empowerment of women cannot truly be achieved.

References:

Baruah, P. (2022). A Short-Spanned Career and a Blurry Future: Migrants from North East India in Hospitality and Retail. Artha- Journal of Social Sciences, Vol.21, No.4.

Kikon, D. & Karlsson, B.G. (2019). Leaving the Land: Indigenous Migration and Affective Labour in India. Cambridge University Press.

McDuie-Ra, D. (2012). Northeast Migrants in Delhi: Race, Refuge and Retail. Amsterdam University Press.

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. (n.d). D-3 (City): Migrants by place of last residence, duration of residence and reason for migration, NCT of Delhi – 2001. Census Digital Library. Retrieved, August 20, 2023, from https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/19565

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. (n.d). D-02: Migrants classified by place of last residence, sex and duration of residence in place of enumeration, NCT of Delhi – 2011. Census Digital Library. Retrieved, August20,2023, from https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/10753

Remesh, B.P. (2012). Strangers in Their Own Land. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol.47, No.22.

________________________________________________

Priyakshi Baruah is a Ph.D. research scholar from Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, Jamia Millia Islamia. Her research interest involves migration, gender and employment with a specific focus on out-migration from North-East India. She also currently works as a Research Associate at V.V. Giri National Labour Institute.