This edition of GenderTalk features a compilation of scholarly research focused on gender and adolescence within the Indian context. Adolescence is a critical developmental stage characterised by significant physical, psychological, and social changes. The experiences and challenges faced during adolescence can have profound and lasting effects on an individual’s well-being, influencing their mental health, relationships, and success in adulthood (Lerner et al., 2002). Gender plays a crucial role in shaping these experiences and outcomes. The way boys and girls experience adolescence can vary significantly, affecting their health, social dynamics, and future opportunities.

India possesses one of the largest adolescent populations globally at approximately 21% of the nation’s total population (Census of India, 2011). This cohort is nearly evenly divided between males and females, though some differences exist due to different birth and survival rates. The adolescent male population is approximately 133 million, while the adolescent female population is approximately 120 million (Census of India, 2011).

India has achieved gender parity in educational enrolment, with the enrolment rate of female students equal to or slightly higher than that of male students at every level of education (UDISE Plus, 2022). While dropout rates are equal between girls and boys at the primary level, they tend to increase slightly among girls as they progress through upper primary level (UDISE Plus, 2022). In rural areas, older girls are more likely to drop out to assist family members with household chores (ASER, 2022). This leaves them with less time for school and leisure activities from childhood through adolescence (Vikram et al., 2024).

India has achieved gender parity in educational enrolment, with the enrolment rate of female students equal to or slightly higher than that of male students at every level of education (UDISE Plus, 2022). While dropout rates are equal between girls and boys at the primary level, they tend to increase slightly among girls as they progress through upper primary level (UDISE Plus, 2022). In rural areas, older girls are more likely to drop out to assist family members with household chores (ASER, 2022). This leaves them with less time for school and leisure activities from childhood through adolescence (Vikram et al., 2024).

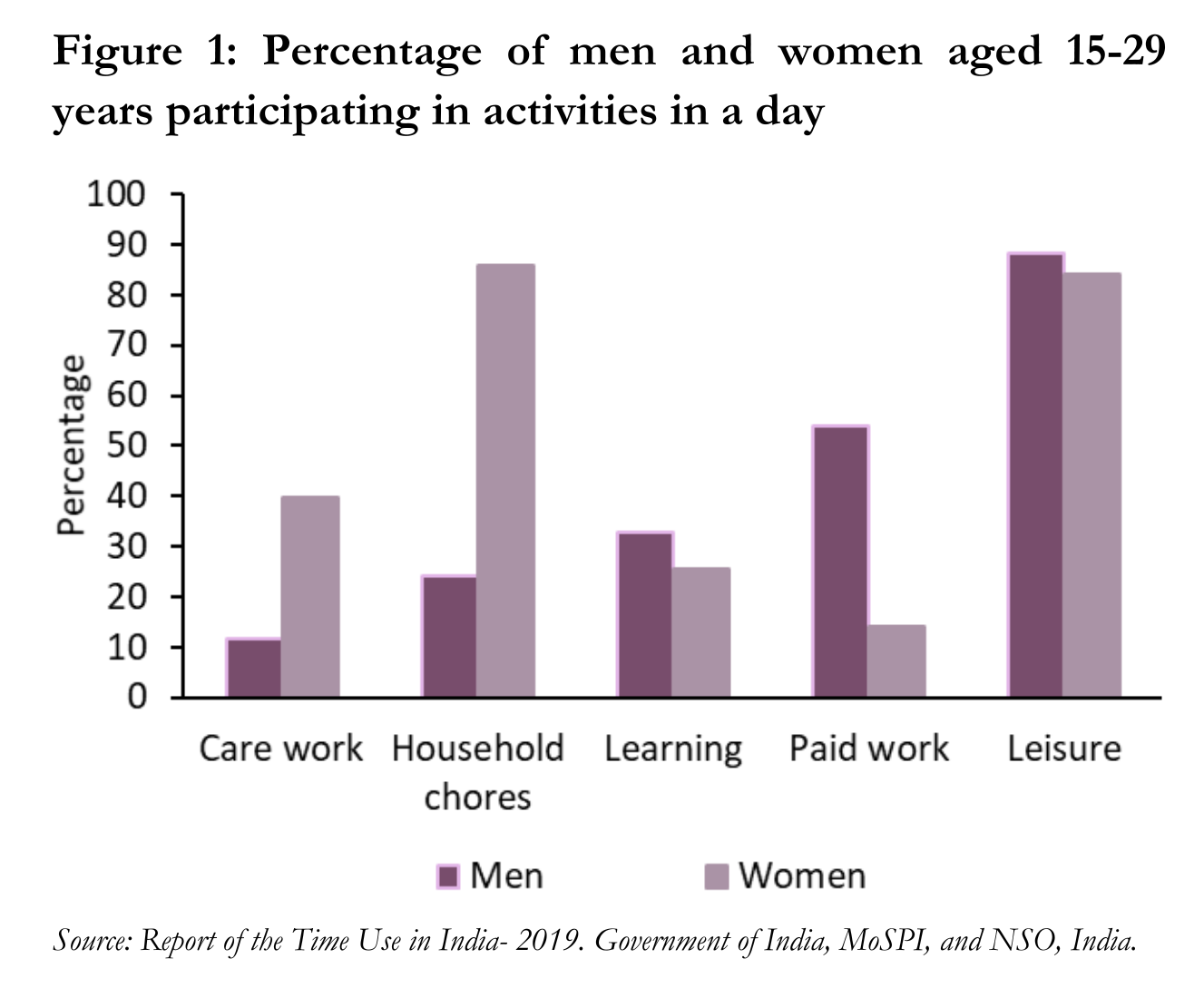

Figure 1 illustrates that among girls and young women aged 15-29 years, only 14% are engaged in paid work, whereas 54% of men in the same age group participate in paid employment. Conversely, 86% of girls and young women are involved in household chores and 40% in caring for other household members, compared to 24% and 12% of boys and young men, respectively. Despite attaining gender parity in education, entrenched gender inequities—perpetuated by the process of gender socialisation, which indoctrinates girls to take on roles as wives and mothers and boys to become providers—continue to impede equitable life opportunities for both sexes.

Figure 1 illustrates that among girls and young women aged 15-29 years, only 14% are engaged in paid work, whereas 54% of men in the same age group participate in paid employment. Conversely, 86% of girls and young women are involved in household chores and 40% in caring for other household members, compared to 24% and 12% of boys and young men, respectively. Despite attaining gender parity in education, entrenched gender inequities—perpetuated by the process of gender socialisation, which indoctrinates girls to take on roles as wives and mothers and boys to become providers—continue to impede equitable life opportunities for both sexes.

However, no national-level data currently captures information on the gender socialization processes and their implications during adolescence, which significantly shape individuals’ futures. A study based on a primary survey provides insights into how parents play an active role as primary influencers in shaping their children’s gender beliefs and instilling gender norms (Basu et al., 2017). Another study using sub-nationally representative data shows that this process of gender socialisation imposes additional constraints on females, limiting their decision-making abilities in daily life, restricting their mobility, and denying them access to financial resources (Ram et al., 2017). Additionally, preferential treatment of males in the household leads to poor mental health for females (Ram et al., 2017). On the other hand, early marriage remains the social norm in India, with approximately 43% of married women aged 15-49 having been married before the age of 18 (IIPS & ICF, 2021). A study conducted in rural areas of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh suggest that less restrictive gender beliefs among adolescent married girls are linked to greater agency and reduced risk of marital violence (Raj et al., 2021). Promoting gender-equitable attitudes from an early age, both within and outside school, with the support of parents and teachers, and challenging harmful gender norms, can reduce the acceptance of violence (Nanda et al., 2020).

Government initiatives such as Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram and Beti Bachao Beti Padhao, targeting the adolescent population, have ambitious and commendable goals. However, impact of any scheme is often limited by implementation challenges, resource allocation issues, and cultural barriers. Addressing these issues requires population-level data to monitor and evaluate outcomes, a multifaceted approach with better resource management, enhanced training, and support for programme implementers, as well as deeper engagement with communities to challenge long-standing gender biases and norms. In the absence of nationally representative data on adolescents, studies based on micro-level data provide insights into the broad spectrum of challenges experienced by adolescents, particularly girls, in India. Comprehensive, nationally representative gender-specific data collection can help identify and prioritise areas necessitating intervention and investment.

The articles in this edition explore topics such as gender socialisation and its adverse effects on mental health, the influence of gender beliefs on the agency of adolescent brides, and how promoting gender-equitable attitudes from an early age can mitigate violence in society. In the Conversation section of this issue, we feature the experiences of a public charitable trust, “Doosra Dashak”, in promoting holistic education and empowering marginalised adolescent girls through active community engagement in remote rural areas of Rajasthan, India.

References

ASER (2022). Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2009 (Provisional). ASER Centre, New Delhi.

Basu, S., Zuo, X., Lou, C., Acharya, R., & Lundgren, R. (2017). Learning to be gendered: Gender socialization in early adolescence among urban poor in Delhi, India, and Shanghai, China. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4), S24-S29.

Census of India (2011). Table B-01: Main workers, marginal workers, non-workers and those marginal workers, non-workers seeking/available for work classified by age and sex (total).

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. (2021). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India: Volume I. Mumbai: IIPS.

Lerner, R. M., Jacobs, F., & Wertlieb, D. (Eds.). (2002). Handbook of applied developmental science: Promoting positive child, adolescent, and family development through research, policies, and programs. Sage Publications.

Nanda, S., Banerjee, P., & Verma, R. (2020). Engaging boys in a comprehensive model to address sexual and gender-based violence in schools. South Asian Journal of Law, Policy, and Social Research, 1.

NSO TUS-2019 (2019). Time Use in India- 2019. Government of India, MoSPI, and NSO, India.

Raj, A., Johns, N. E., Bhan, N., Silverman, J. G., & Lundgren, R. (2021). Effects of gender role beliefs on social connectivity and marital safety: findings from a cross-sectional study among married adolescent girls in India. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(6), S65-S73.

Ram, U., Strohschein, L., & Gaur, K. (2014). Gender socialization: Differences between male and female youth in India and associations with mental health. International Journal of Population Research, 2014(1), 357145.

UDISE plus (2022). Report on Unified District Information System For Education: Flash Statistics. Government of India.

____________________________

Dibyasree Ganguly, a Post-Doctoral Fellow at NCAER’s National Data Innovation Centre, specialises in gender, time-use, health, and well-being research. She holds a PhD in Regional Development from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She has published research articles in prestigious journals including Social Science Research, International Journal of Epidemiology, and Child Indicators Research.

![]()